Removing Barriers to High Reliability

Creating a Culture of Safety

Given high rates of adverse events, process failures and patient harm, the idea of achieving high reliability in healthcare may seem absurd. Even so, many well-respected healthcare leaders have sounded the clarion call to make this the primary goal. I believe it can be done, but not without a major shift in organizational culture.

Quality and Safety Improvement Framework

Safety and high reliability are key components of patient-centered care. They fulfill the Hippocratic dictum, Primum Non Nocere - First, do no harm. It is incongruous that the majority of physicians and nurses are not well-engaged in the pursuit of patient safety. To both explain and find a way to overcome this barrier to progress, we need to look at the prevailing culture particularly as it pertains to adverse event analysis.

Despite naysayer protests that healthcare is different, we have much to learn from the amazing advances that were achieved in aviation safety as a result of engaging pilots in crew resource management and self-reporting of near misses and hazardous conditions. The result was a seismic shift in culture away from "Captain is King" to teamwork and from cover-up to transparency and commitment to safety.

Reporting and teamwork are complementary. Reporting is essential to mobilize organizational resources to address problems that cannot be quickly solved by the work unit. Good communication within the team is essential to maintain mindfulness for the unexpected and to enable a rapid response to contain any emerging threats to safety. Most organizations will likely find greater leverage in focusing initially on self-reporting, if only because staff training for better communication (e.g., TeamSTEPPS) is resource intensive and requires ongoing practice to be sustained. Thus, the benefit of team training should be greater when it occurs in an environment that is actively promoting self-reporting and, thereby, raising awareness of safety issues.

I have conducted four national studies of clinical peer review including an eight year longitudinal follow up of programs at 270 hospitals (In Pursuit of Quality and Safety: an Eight-Year Study of Clinical Peer Review Best Practices in U.S. Hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. (published Online First: April 9, 2018) doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069). Together with the four year follow up study (published in the September/October 2013 issue of the Journal of Healthcare Management and summarized in Becker's Hospital Review) it offered the first large-scale demonstration that self-reporting is beginning to be embraced in healthcare and is having a strongly positive impact on quality and safety.

But these studies also showed that the dysfunctional and punitive QA model for peer review, which mistakes performance for competence, still dominates practice. This is a big problem with respect to the goal of high reliability. Clinical peer review among physicians and among nurses and their managers is the primary method of event analysis in US Hospitals. Who in their right mind would voluntarily self-report an adverse event, near miss or hazardous condition and risk flagellation, censure or worse? Despite a high rate of change, very few programs have fully-adopted the best practice QI model which corrects this dysfunction and opens the door to a culture of safety.

I've created a storyboard to assist healthcare leaders understand and communicate what is required to initiate sustainable progress toward a culture of safety and embrace the potential for high reliability: High Reliability Storyboard.

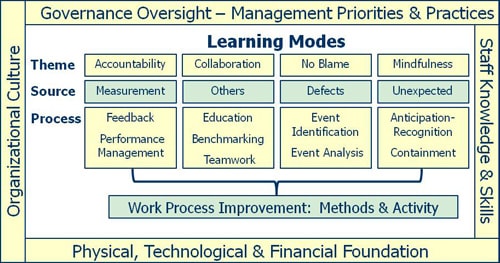

By intent, the storyboard is dense. It assumes familiarity with, but not mastery of, QI and safety principles. It pulls from the work of many pioneers, including Deming, Juran, Crosby and Weick. Whether you hold that quality is conformance to requirements or fitness for use doesn't so much matter, as long as you appreciate that the real work of quality improvement involves attention to organizational processes as well as training and engagement of frontline staff. I believe it's most useful to think about quality, safety and high reliability in terms of the conceptual framework of a learning organization (see above graphic). From this, it's not hard to see that the four major modes of organizational learning touch the heart of what matters most in healthcare: delivering ever-improving patient care.

While some might view QI more narrowly, I believe there is much more potential benefit from QI than just looking good on performance measures promulgated by the Joint Commission, CMS and others. The key activity of QI is standardization of work processes to reduce variation, eliminate waste and minimize the impact of human fallibility, especially with respect to diagnosis, treatment and handoffs of care. Elimination of waste goes directly to the financial bottom line, as does reduction in harm. Quality and safety drive reputation. This includes the way we express care and concern for patients and their families through our interactions with each other and with them, as well as the way the facilities look and how they operate. Reputation matters, even if its hard to quantify. It augments the pride, teamwork and sense of ownership that would otherwise come from QI activity.

In general, I subscribe to the philosophy that leadership is a verb and that organizations are strengthened by fostering leadership behavior at all levels. Nevertheless, you'll find that the first two points on my list of the requirements for high reliability use the term "management." I adapted them from Deming and I believe they are still relevant. Those appointed to management positions control resources and have formal power, regardless of how well they lead others. If senior management does not know what to do and does not lead the way, it is highly unlikely that informal leaders lower in the hierarchy will succeed in fostering the needed transformation.

Healthcare leaders from other countries may use the terms QA and QI differently than we do here in America. If so, I apologize in advance for any confusion this might create. The QA process has an unfortunate history here (see QA Model History). In the late 1970s, America abandoned the clinical audit model, which has to a great extent been preserved elsewhere. I believe that if we look together at the detail of what is represented by what I call the QA Model (see QI and QA Models Compared), we are highly likely to agree that it is dysfunctional and hostile to a culture of safety. Regardless, I do not wish to cause offense to any who use the term Quality Assurance to refer to healthy, non-punitive improvement-oriented processes.

For more than a decade, there has been much interest in Just Culture. Fundamentally, the Just Culture model seeks to create accountability for behavior choices and no blame for human error. In contrast, the storyboard emphasizes the no blame part, because the context is learning from defects (see above graphic) and because a culture of blame is the primary barrier to high reliability. Healthcare organizations characteristically have trouble with accountability too. Even so, accountability is better pursued via the learning from measurement (including observation and other means of assessment), which proceeds through feedback and performance management activity.

There is danger in trying to address both no blame and accountability through the same program. Particularly in the setting of adverse events, the probability of reckless disregard of patient safety is too low to support any policy other than initial presumption of staff innocence. I'm concerned that too many supervisors either get confused with the Just Culture algorithm or pervert it to justify continued punishment of staff. It's quicker and more emotionally satisfying to cast blame when something goes wrong than to do the harder work of getting to the root of the problem and fixing the related processes.

Furthermore, Just Culture is a legalistic framework. Even if it serves the purpose of management to help identify blameworthy acts, it does not speak to the heart of healthcare workers. While hospital leaders frequently believe Just Culture has had a positive impact, there is no objective evidence that wholesale adoption of Just Culture across the US has been effective in reducing blame for human error or increasing reporting of problems (An Assessment of the Impact of Just Culture on Quality and Safety in U.S. Hospitals. Am J Med Qual. (published Online First: April 16, 2018) doi:10.1177/1062860618768057).

Many thanks go to John Chessare, MD, CEO at Greater Baltimore Medical Center, Barbara Price, SVP Clinical Operations at Scripps Health, Chad Whelan, MD, Associate Chief Medical Officer for Performance Improvement and Innovation at the University of Chicago, Ross Wilson, MD, CMO at NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation, Michael Hein, VPMA at Saint Francis Medical Center, Grand Island, Susan Went of Nerissa Healthcare Consulting, London, England, Pam Jones, DNP, RN, CNO at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Laura Wood, DNP, MS, RN, CNO at Boston Children's Hospital, Carole K. Dalby, RN, MBA, OCN, CCRP of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston and Richard Pitts, DO, PhD, Interim CEO at Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, among others for their thoughtful suggestions for improvement.

Links

- High Reliability Storyboard

- Clinical Peer Review Program Self-Assessment Inventory

- Clinical Peer Review Process Improvement Resources

- The QI Model

- Ideal Clinical Peer Review Process Collaborative

- Normative Peer Review Database Project

Products & Services

- The Peer Review Enhancement ProgramSM

- DataDriverSM Accelerated Improvement

- PREP-MSTM Program Management Software

- My PREPTM Toolkit for Peer Review Program Improvement

- Client Testimonials

- Typical Client Results

Whitepapers