Every cook needs a knife. Lucky me to have a friend like Marlene who saw the opportunity to bestow the perfect house-warming gift.

Duncan Stephenson is a master craftsman who specializes in kitchen knives. Marlene knew I was not happy with my ancient kitchen knives. By chance, she met Duncan at a gallery show in downtown Raleigh over the holidays. She was impressed with his craft but kept quiet about it. So, I was totally surprised when she proffered a gift box containing a black cotton t-shirt with Duncan’s logo and a certificate for a custom Nakiri.

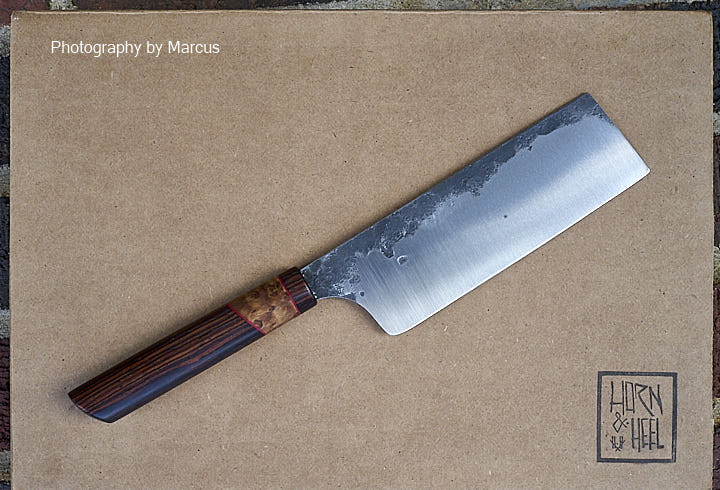

A sense of dread replaced that surprise when I checked out his website. His knives artfully combine wood and metal, but they’re pricey. I was worried that her gift might be impractical for my purposes and would end up framed on the wall. Little did I know.

Meeting Duncan Stephenson

When I contacted Duncan about the gift certificate, he invited me to meet him at Quercus on Monday, January 15. Quercus is a boutique in downtown Raleigh that showcases his work. As it was a holiday, I didn’t have any trouble with traffic or parking. In fact, most of the shops were closed, including Quercus, yet as I approached the door, I found a diminutive, tattooed man in overalls there to greet me.

He indicated that it would take about three months to get my knife given his backlog of work from holiday sales. That was no problem for me since I intended to save it for the inauguration of my new home. Then he began to feel me out as to what I wanted and how I expected to use it. Over the next hour and a half, we went over samples of his work and discussed options for innumerable details of the knife’s construction—shape, length, weight, type of steel, handle composition, shape & size, etc. Along the way, I asked many questions and shared some of my fears, such as whether the tapered tang that he favors would leave the handle vulnerable to loosening over time (answer—not on account of the industrial strength epoxy he uses to bond them together).

I also shared relevant aspects my Ayurveda practice and cooking classes. My related preference for things Sattvic drove some of the decisions. For example, Duncan often uses spalted wood in his handle design for its interest and beauty. Spalted wood results from fungal decay. Therefore, Duncan pressure-treats it with a plasticizer for stability. Decay is the antithesis of Sattva, so that was out.

Similarly, chefs often favor high-carbon steel because it best holds a razor edge. On the other hand, because it rusts easily and reacts with acidic foods, it requires more care than stainless steel. Duncan thought it would be a poor choice for me. Even if I religiously wiped it dry after use, I could still expect it to take on a patina that might not be perceived positively by guests. He reassured me that the German razorblade stainless steel he would prefer to use would not disappoint.

It was a lot of information to absorb at one time. The encounter convinced me, however, that Duncan is not only an artist but a master of the craft of aligning form and function.

Having had a career in medicine and health care management, I’m no stranger to decision-making or to the consequences of having to live with the results. The process of designing and building my Vāstu home strengthened that discipline, especially the part about exploring options. Not infrequently, I would revisit those decisions several times to validate and get comfortable with them. A few days after our meeting, I sent this email:

Duncan,

Thanks again for meeting with me on Monday. You are truly a fountainhead of knowledge. I appreciated your patience with my many questions.

I’m excited about the knife, though with all the decision points, still a little apprehensive that we got them all right. A thought exercise even with some great examples in the hand is still not the same as a kitchen test.

Though really the only thing that stands out as possibly benefiting from reconsideration is the blade weight. It’s my only significant doubt.

The heftier one was certainly too hefty. The one with the ellipsoid handle was very good, but could it be too light for general-purpose use on vegetables and fruits? That is, would it be as great for hard squashes, sweet potatoes, etc. as for leafy greens, okra, zucchini etc.? Is there anything in between to consider?

If not, or if this is splitting hairs, then you can just reassure me.

Stainless over carbon is definitely right, as is the larger diameter ellipsoid handle.

As for the wood – I like the idea of cocobolo. Red is an auspicious color in Japan. Would cocobolo work with something on the blond side like maple for an accent? If not, maybe a nicely figured piece would shine by itself?

He promptly replied:

I believe we are splitting hairs a bit when it comes to the weight. There are many variables that influence the weight of the knife; the handle material’s density, the length, width, and thickness of the blade and handle, the grind geometry, amount of epoxy, etc.

I have a good feel for what kind of knife you need. I am going to create a blade that is going to perform well for what you are looking for, all the while keeping in mind the weight when I attach the steel to the wood.

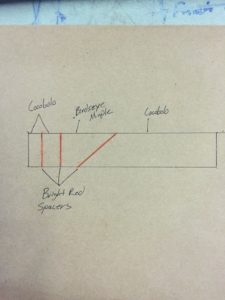

I think a piece of either curly or bird’s eye maple would look fantastic paired with the cocobolo.

Cheers, Duncan

Three weeks later, I got this note and photos:

Forged, profiled, and heat treated. I’ve attached an image of what I have in mind for the composition for the handle. Not the shape, just the wood proportions. As well as the cocobolo and maple next to the spacer I have in mind.

Pick Up Time

I was surprised again when little more than a month from our meeting, Duncan told me my knife was ready for pick up. This time we met at his workshop. For me, an old-time woodworker, it was a special treat to tour his digs and watch him in action.

I also got a tutorial in knife sharpening. He has a simple, but pricey tool that allows him to hone a newly forged blade to perfection in a matter of minutes. He recommended the WorkSharp system, which he also has, as a more affordable alternative.

In anticipation of getting a real Nakiri blade, I had been using a Japanese-style knife from Marlene’s Pampered Chef collection with a large, ergonomic composite handle—nice enough, but no match for Duncan’s craftmanship. When I first saw my Nakiri, I was awed by its beauty, yet when I picked it up, the handle felt too small and delicate. I stuffed my apprehension that Duncan had taken too much weight off the handle. It cut through his testing potato like butter. I rightly concluded the only way I’d know for sure was to start using it in my own kitchen. For that I had to wait another 10 weeks.

The Best Knife I Ever Used

From the start, my Nakiri was a joy to use. When slicing fruits or vegetables, you push straight down and feel the click on the cutting board. There is no need to rotate your wrist as with a French chef’s knife. The cuts are clean and as thin as you’d like. The square end of the blade is handy for pushing cuttings into the sauté pan (Duncan warned me that my old habit of using the blade edge for that purpose would dull it more quickly). And yes, it was perfectly balanced and weighted for my needs.

After the first month I needed to tune it up with my WorkSharp, but only with the accessory kit’s extra fine plate, followed by a honing strap. I still have occasional use for my Cutco collection (a gift from my brother Brian at least 40 years ago), primarily the paring knife (separating mango skin from the seed-containing slice) and medium serrated knife (slicing figs, dates and carrot cake). Otherwise, it’s my Nakiri for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Thank you, Marlene. Thank you, Duncan.

PS: Duncan Stephenson was also profiled in the May 2018 issue of Walter Magazine